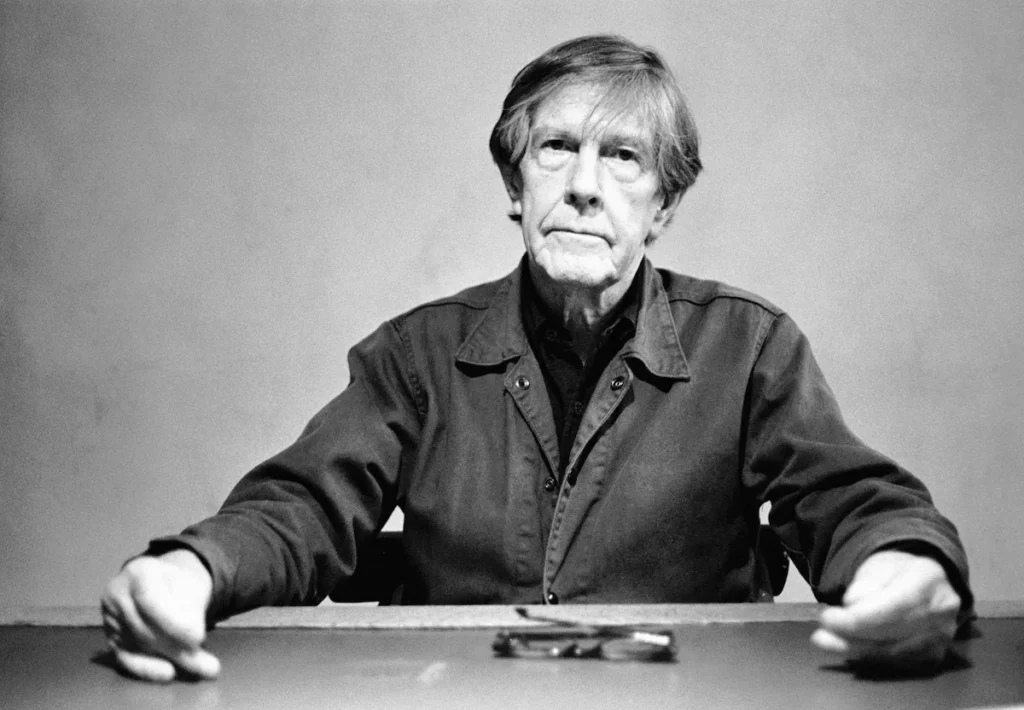

“Experimental” is the term most often used describe the music of John Cage. But for those who have never heard nor seen a Cage performance, the term experimental says little.

Mozart was experimental. Miles Davis was experimental. The Beatles were experimental. But when the word is applied to John Cage, “experimental” takes on an entirely different dimension.

Heavily influenced by artists outside the field of music (like dancer/choreographer Merce Cunningham and painter/pop artist Robert Rauschenberg), Cage considered music a form of art that does not rely on expressing something from within the composer, but something that already exists around him/her.

Cage’s first “experimental” music involved altering standard instruments, such as placing plates and screws between the strings of a piano before playing it. But as his alterations of traditional instruments became more elaborate, he came to realize that what he actually needed were entirely new instruments; perhaps needed to think of various objects and devices as instruments in and of themselves.

For his piece, “Imaginary Landscape No 4,” for example (composed in 1951), Cage incorporated 12 radios played simultaneously; the piece depending entirely on what happened to be broadcast at the time of performance.

Similarly, for “Water Music” (composed in 1952), Cage utilized a water pitcher, goose and quail calls, an iron pipe, a deck of cards, five radios, a bottle of wine, an electric mixer, a bird whistle, a sprinkling can, a mechanical fish, ice cubes, two cymbals, a rubber duck, a vase of roses, a tape recorder, a seltzer siphon, and a bathtub. (A grand piano was present, manipulated for unusual sounds—or there simply as a visual prop.)

In Cage’s own words, “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating. The sound of a truck at 50 mph; static between the stations; rain. We want to capture and control these sounds, to use them, not as sound effects, but as musical instruments.”

By the time of his death in 1992, Cage’s musical creativity took on dimensions never anticipated by his early creations. Despite (or perhaps because of) his “experimental” approach to music, his contributions to music, dance, and art cannot be overstated; his legacy both brilliant and incomparable.

Early Life

John Milton Cage, Jr., was born on September 5, 1912, in downtown Los Angeles, California, to John Milton Cage, Sr., an inventor, and Lucretia, “Crete” Harvey, a journalist for the Los Angeles Times.

Most of what is known about Cage’s early life and family comes from Cage himself; either in his writings or product of various interviews.

As a child, Cage was introduced to music by members of his family—initially, his aunt Phoebe Harvey, who exposed him to 19th Century piano music—then began taking proper piano lessons in the 4th grade.

In an interview with biographer Richard Kostelanetz in 1976, Cage stressed his very “American” roots,

noting that (future President) George Washington was assisted by one of his ancestors (also named John Cage), in the task of surveying the Colony of Virginia in 1748.

In describing his parents, Cage portrayed his mother as a woman with “a sense of society [who was] never happy,” explaining that his father was perhaps best characterized by his inventions and ideas: such as a diesel-fueled submarine that gave off exhaust bubbles (the senior Cage was disinterested in an “undetectable submarine”), and his explanation of the cosmos he referred to as the “Electrostatic Field Theory.”

Cage quoted his father as telling him as a boy, “If someone says can’t, that shows you what to do.”

Education

In 1928, at the age of 16, Cage graduated from Los Angeles High School, planning to pursue a career as a writer.

After graduation, Cage enrolled at the Pamona College, in Claremont, California, where he attended classes until 1930–then dropped out. Convinced that a college education is not important to someone intending to be a writer, he determined that travel and world experience would be far more beneficial.

Europe

For the next 18 months, Cage traveled throughout Europe, visiting France, Germany, and Spain—his first musical compositions manifesting while in Majorca. During his travels, Cage also experimented with various other forms of art including poetry, painting, and theater.

While in Europe, Cage heard the music of contemporary composers like Igor Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith for the first time, and discovered the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Late in 1931, Cage returned to the US, locating in Santa Monica, California.

Coming into His Own

While living in Santa Monica, Cage earned a living lecturing on contemporary art. During this time, he became known to a number of prominent personalities of the Southern California art community, including pianist Richard Buhlig (who became Cage’s first composition teacher) and Galka Scheyer, a local patron of the arts and supporter of budding new artists.

In 1933, Cage decided to focus on music rather than the other art-forms he’d been experimenting with (primarily painting). As he would later explain, “The people who heard my music had better things to say about it than the people who looked at my paintings had to say about my paintings.”

That same year, Cage sent his few of his compositions to renown composer Henry Cowell, who suggested he seek instruction from pianist/composer Arnold Schoenberg (well known for his work with atonality and his “twelve-tone method”). He further suggested that Cage first seek instruction from Adolph Weiss, a former student of Schoenberg, before approaching Schoenberg himself.

Following Cowell’s suggestion, Cage moved to New York City and started taking lessons from Adolph Weiss (as well as Henry Cowell) at the performing arts college, The New School; supporting himself by washing walls at the Brooklyn YWCA.

Some months later, when he was sufficiently confident of his compositional skills, Cage approached Schoenberg and subsequently studied under him; first at University of Southern California (USC), then at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Marriage

Sometime during his time with Schoenberg (1934-1935), while working at his mother’s arts and crafts shop, Cage met artist Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff; an Alaskan-born daughter of a Russian priest. Her work encompassed fine bookbinding, sculpture, and collage art. Although Cage was maintaining a sexual relationship with Australian architect Rudolph Schindler’s wife, Pauline, he proposed shortly after meeting Kashevaroff. He and Kashevaroff were married in Yuma, Arizona, on June 7, 1935.

A Budding Career

From 1936 to 1938, Cage worked at many jobs, including as a dance accompanist at UCLA—which began his lifelong association with modern dance. He also composed music for choreography and taught a program called, “Musical Accompaniments for Rhythmic Expression” at UCLA.

It was during this time that he began to experiment with unorthodox “instruments” such as metal sheets and random household items for the first time. Also about this time, the work of Oskar Fischinger caught his attention; a German animator experimenting with the relationship between sound and image.

In 1938, with the help of experimental musician Lou Harrison (a fellow student of Henry Cowell), Cage joined Mills College as a faculty member. As several modern dance groups were based at Mills, Cage had the opportunity to collaborate with several dance instructors including choreographer Marian van Tuyl; Cage becoming increasingly more interested in modern dance.

After a few months at Mills, Cage moved to Seattle, Washington, where he worked as a composer and accompanist for Bonnie Bird, the head choreographer at Cornish College of the Arts.

By 1940, Cage’s experimentation with unconventional instruments brought him both acclaim and respect, particularly with the invention of the “prepared piano.”

The “Prepared Piano”

Bringing to fruition an idea Cage had been working on since 1938, the “prepared piano” is essentially a piano that has been modified by inserting various objects (which Cage termed “preparations”) between, on, or under the strings. These “preparations” range from bolts and screws to rubber erasers; fabrics, and even cutlery—depending on the desired effect.

Cage discovered that by selecting particular objects and placing them in specific locations, the piano’s sound is altered in a number of ways–from muting strings to generating harmonics and overtones—resulting in a completely unique, percussive sound, not normally associated with traditional piano.

Initially born of necessity rather than experimentation, Cage had intended his composition “Bacchanale” (written in 1938) to incorporate an ensemble of percussion instruments, but due to the size constraints of the performance room, decided to place various objects inside the piano to create a percussive effect.

Hailed as ingenious by his contemporaries, the “prepared piano” was incorporated into contemporary Classical music of the time, and found its way into Jazz, Rock, and electronic music in more recent years.

The “prepared” method has also carried over to other stringed instruments like the guitar and harp.

Chicago

In the summer of 1941, famed Hungarian painter and photographer (and professor at Bauhaus school of design in Germany) asked Cage to teach at the Chicago School of Design. Relocating to Illinois, Cage was then offered a position at University of Chicago as a resident composer and accompanist.

Soon after, his fame as a percussion composer gained him a commission from the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) to create a soundtrack for a radio play by poet Kenneth Patchen: The City Wears a Slouch Hat. Well received by listeners and critics alike, Cage decided it was time to seek greater opportunities in New York City.

New York City

Arriving in New York City in the spring of 1942, Cage and his wife made the acquaintance of surrealist painter Max Ernst and his wife, Peggy Guggenheim (wealthy patron of the arts). The couple introduced Cage to several renown artists including Piet Mondrian, Andre Breton, Marcel Duchamp, and Jackson Pollock (whose first one-man show Guggenheim had financed).

Although Guggenheim was a great fan of Cage’s work, and even offered to organize a concert of his work at her gallery, Art of This Century, when Cage agreed to perform at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) as well, she took it as an act of betrayal—and withdrew her support. And while his performance at MOMA was a critical success, offers for commissions didn’t come in as expected and he was soon destitute.

Staying temporarily with modern dance choreographer Jean Erdman and her husband, professor of literature, Joseph Campbell, Cage began composing “prepared piano” performance pieces for choreographer Merce Cunningham; with whom he would become romantically involved. (Cage’s marriage would end in 1945, while he and Cunningham would remain together for the remainder of Cage’s life.)

Mid-Life Crisis and Eastern Influence

Although Cage had experienced minor successes in the 1940s (the popular The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs in1942, a song for voice and closed piano performed by popular duo, Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio; and had appeared in experimental filmmaker Maya Deren’s At Land, a 15-minute silent film in 1944), he also experienced a growing disillusionment with the idea of music as means of communication. He came to realize that only a small minority of the public appreciated his work, and that he himself had trouble comprehending the music of his fellow experimental composers.

In early 1946, Cage agreed to tutor Indian musician Gita Sarabhai, who’d come to the US to study Western music. In return, Cage asked Sarabhai to teach him about Indian music and Eastern philosophy.

The first fruits of this interaction were the Indian-inspired works, Sonatas and Interludes for “prepared piano” (a piece Cage dedicated to Armenian-American pianist/accompanist Maro Ajemian) and String Quartet in Four Parts. Cage would later say that he came to accept as true, Sarabhai’s philosophical perspective that the goal of music is “to sober and quiet the mind, thus rendering it susceptible to divine influences.”

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Cage began attending lectures by Zen Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki, and began studying the works of Eastern metaphysician, Ananda Kentish Muthu Coomaraswamy.

Early 1950s

By late 1949, pianist Maro Ajemian (along with her sister, violinist Anahid Ajemian), became known as a champion of new music, premiering many works by American composers–including Cage. Cage had dedicated Sonatas and Interludes to her (and by some accounts, she’d performed it at New York’s Carnegie Hall) and she’d made the first recording of it for Dial Records in 1951. This attention to his work garnered Cage a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, which enabled him to make a second trip to Europe, where he met French composers Olivier Messiaen and Pierre Boulez.

In early 1950, Cage had a chance encounter with American avant-garde composer Morton Feldman; both men having attended a New York Philharmonic performance of Anton Webern’s Symphony, Op. 21, and a piece by Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Bumping into each other in the lobby, the two became fast friends, subsequently becoming part of a small group of highly respected new composers (that included Feldman, Earle Brown [creator of the “open form” style of composing], and David Tudor) regarded as leaders in the avant-garde, experimental music movement.

But despite the critical acclaim Sonatas and Interludes received, and the connections he’d cultivated with American and European composers and musicians, Cage remained quite poor. In fact, by 1951 his financial situation had become so dire that while working on his Music of Changes (a piece Cage devotees describe as his most complete use of “chance elements” in composition), he prepared a set of instructions for David Tudor as to how to complete the piece in the event of his death.

1952: Theater Piece No. 1 and 4’33”

Theater Piece No. 1 was Cage’s first large-scale collaborative, multimedia performance piece, created and performed while teaching at the avant-garde Black Mountain College near Ashville, North Carolina, where he taught during the summer sessions of 1948 and 1952.

The piece (often referred to as an “event”) involved several simultaneous performance components, with chance played a determining role in the course of the performance which included: poetry readings, dance, film, music, photographic slide projections, and the four panels of Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings (1951) suspended from the ceiling in the shape of a cross—during which Cage sat atop a step ladder and lectured about Buddhism; or sometimes, said nothing at all.

By contrast, 4’33” (also composed at Black Mountain), a three-movement composition that doesn’t contain a single note of music, depended entirely on the environment in which it’s performed–and elements of chance.

Instead of using a number of performers working in cooperation or tandem for this piece, Cage provided detailed instructions for a single musician to: enter the stage, prepare his/her instrument (initially a piano, but other instruments have since been used), and then sit absolutely silent for the duration of the piece–4 minutes and 33 seconds. It is the performer’s utter silence that allows the sounds of the surroundings and audience members to essentially compose the “music.”

Publishing, Fame, Demand

From 1956 to 1961, Cage taught experimental composition at The New School, in New York City.

Among the more important works completed during this period are, Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957–1958), and Variations I (1958).

Also affiliated with the private liberal arts college Wesleyan University, in Middletown, Connecticut, in 1960, Cage was appointed a fellow on the faculty of the “Center for Advanced Studies,” where he taught classes in experimental composition.

In October of 1961, Wesleyan University Press published Silence, the first of six books Cage would write in his final years; a collection of lectures and writings on a variety of subjects–including his now famous, “Lecture on Nothing.”

The following year, Cage drew the interest of Edition Peters, a Classical music publisher based in Germany, who subsequently published a large number of his scores—which, along with publication of Silence, gave him fame and prominence in Europe and America.

By the mid-1960s, Cage was receiving so many commission offers and requests for appearances that he was unable to fulfill them.

For the remainder of the 1960s, Cage’s work reflected the philosophical and sociological mood of the era—resulting in what many consider his most ambitious pieces (whose live presentations were commonly referred to as “happenings”).

Cheap Imitation

In 1969, Caged composed what was both a departure from his established experimental compositional style, and the piece that for many came to define him: Cheap Imitation, a piece for solo piano.

An evolving, highly collaborative piece that seemingly became his obsession–ultimately requiring an orchestra (minimum of 24 instrumentalists, maximum of 95) and a violin soloist, and featuring a highly complex, choreographed dance)–Cage performed the piece into the mid-1970s; when severe arthritis prevented it.

(But that didn’t prevent him from further developing the piece for the remainder of his life.)

Final Years

In many regards, the final decade of Cage’s life was the most productive:

During the 1980s, he wrote dozens of pieces dedicated to various performers he admired (such as a piece for flute and piano called Two, dedicated to flutist Roberto Fabbriciani); wrote five operas between 1987–1991, all sharing the same title, Europera; composed some 40 “Number Pieces” (as they came to be known); made his only venture into film-making, a monochrome art film titled, One11; and began a collaborative work called, ONE13, for violoncello, with curved bow and three loudspeakers.

This final decade, however, also saw the progressive deterioration of Cage’s health; crippling arthritis followed by sciatica and arteriosclerosis.

In 1985, Cage suffered the first of two serious strokes—which limited the use of his left leg.

On August 11, 1992, Cage suffered his second stroke and was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan, NYC. The following morning, John Milton Cage, Jr. died from complications from heart failure. He was 79 years of age.

References:

www.pbs.org., “John Cage Biography,” John Cage | John Cage Biography | American Masters | PBS

sound-art-text.com., “John Cage ‘Water Music’,” https://sound-art-text.com/post/29753771316/john-cage-water-music

britannica.com., “John Cage,” John Cage | American Composer & Avant-Garde Innovator | Britannica

moma.org., “John Cage, American, 1912–1992,” John Cage | MoMA

artnet.com., “John Cage,” John Cage Biography – John Cage on artnet

thefamouspeople.com., “John Cage Biography,” John Cage Biography- John Cage Childhood, Life and Timeline (thefamouspeople.com)

hellomusictheory.com., “The Prepared Piano,” https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/what-is-a-prepared-piano/

theartstory.org., “John Cage,” https://www.theartstory.org/artist/cage-john/