When British “outsider artist” Ron Gittins passed away in 2019 at the age of 79 (“outsider” the term referring to artists primarily self-taught), family and friends had no idea what to expect when they entered his rented apartment in Oxton, Birkenhead, England; but knew it would be fantastic.

Even as a boy living in his parents’ home at Beta Close, Merseyside, England, Gittins had transformed his bedroom into a replica of a Roman villa, and during the mid-70s, caught the attention of the Liverpool-based daily newspaper, Liverpool Echo, which subsequently ran a feature article titled, “Pictures of Pompeii Help Put Ron to Sleep” (along with a photograph of the bedroom walls and ceiling painted with Roman scenes and likenesses of emperors).

From 1986 until his death, Gittins lived alone at 8 Silverdale Road, Oxton, the terms of his lease originally providing him a free-hand at decorating the apartment as he chose–without the need to seek landlord approval. (He did, however, perform much of his work in secrecy as many of his modifications weren’t strictly legal.)

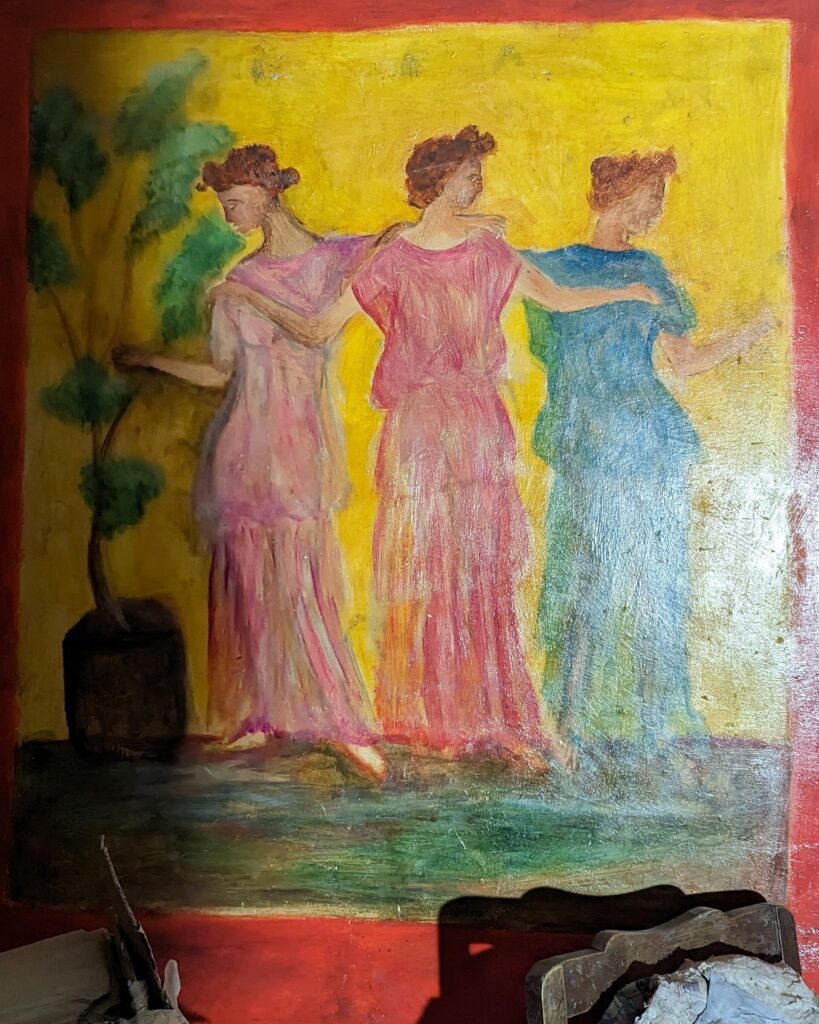

Over the course of 33 years, Gittins painstakingly transformed the entire apartment–almost every visible surface–with an array of artwork in a variety of styles and mediums–from lifelike friezes on the living room walls to a Roman altar in his kitchen; to the installation of enormous Greco-Roman style columns.

After his passing, local residents (most of whom had never caught even a glimpse of his interior masterpiece) remembered him as a familiar sight, shuffling along the streets of Oxton Village dressed in a selection of homemade military costumes, pushing an old-fashioned baby pram filled with bags of cement he used to build (among others features) his gigantic, fully-functioning fireplaces.

Childhood

Ronald Geoffrey Gittins was born in Birkenhead, England, in 1939; one of three children born to James Gittins (a Navy man who worked on the docks and known to keep ducks in the back yard), and Alice (a maid for a well-to-do family).

Remembered as a boy who amused himself by reciting Shakespeare monologues, his family knew from an early age that Gittins was going to have a difficult time “fitting in” life. His interests were all his own.

Recognized as having a gift for music, Gittins sang in the church choir; and was reportedly clever at imitating American Rock-a-Billy singer, Buddy Holly.

Education

Although Gittins showed obvious signs of intelligence as a primary school student, his teachers weren’t sure which direction to guide him; he seemed to have no aptitude for academics whatsoever.

As a result, Gittins was provided a varied education including brief attendance at the Laird School of Art (where he learned the basics of art and design), and when he was 20 years of age, trained as a Methodist minister at Cliff Bible College in Derbyshire, England.

Finding His Niche

After theology college (it’s not certain that he completed his studies), Gittins took to the street, becoming (for all intent and purposes) a freelance preacher; most finding his aggressive demeanor annoying. This began a long succession of jobs—none of which he seemed especially suited to.

For a time, Gittins was a cutter in a printing shop; then worked in retail in Liverpool. Then at some point he worked as a quality control officer for a home appliance company—but always sided with management over the employees; which made him quite unpopular with co-workers.

Eventually becoming a familiar face around London, Gittins is said to have performed with local amateur drama groups, at one point (the time-line isn’t clear) became a self-employed artist, and sometime later on, established Minstrel Enterprises, a business featuring himself as “The Minstrel.”

Trying to stand out in a crowd, Gittins began dressing more and more outlandishly–wearing bright handmade suits and wigs (sometimes more than one at a time). Most who got to know him considered him odd—but basically harmless. He seemed bright, fascinated with the goings-on of the world, and offered his help when he could.

But when Gittins starting taking his guitar to the local bank to serenade the staff, his friends began thinking he was more than just “eccentric.” They questioned his sanity.

(In later years when he professed to be a spy whose job it was to intercept messages hidden in newspaper articles, no one was surprised; some even found it entertaining.)

“Ron’s Place”

In 1986, at the age of 47, Gittins discovered the apartment (the first floor of a Victorian duplex comprised of three main rooms, a hallway, kitchen, and a bathroom) where he’d spend the remainder of his life—and dedicate his seemingly inexhaustible imagination and energy.

The third such space he would transform (the first, his bedroom at his parents’ rented house; the second, the ceiling of a single room he’d rented), the Victorian apartment, located in the village of Oxton in Birkenhead (just outside London), made Gittins’ previous artistic endeavors look like mere rehearsals.

Becoming a veritable recluse once the work began, Gittins’ comings and goings became fodder for speculation and gossip among the townspeople; him in his strange costumes seemingly assembled from rags and discards—appearing and disappearing into his secret world.

Those who entered the massive work after the artist died (he discouraged visitors and few had ever been formally invited inside) found it impossible to ascertain where the work began and ended; the organic quality of Gittins’ creation enveloping everyone inside.

The “Outsider” Tradition

“Outsider art” (“folk art” and “art brut”) is the term applied to artists who have no formal (or limited) training, who work outside traditional methodologies of art; and quite often, outside the law—which could apply to many spray paint street artists.

When “outsider” work is a large-scale installation (as is the case with Gittins), permanent or semi-permanent, it’s often referred to as an “outsider environment” or “visionary environment.”

Many such artists around the world have achieved acclaim through various forms of “outsider” artistic expression; expression some have difficulty validating as art.

For example, a former monk living outside Madrid, Spain, named Justo Gallego Martínez, spent 60 years single-handedly building his own cathedral; working on it daily until he died in 2021.

In Westbourne Grove, London, England, a retired postal and factory worker named Gerry Dalton, created a series of extraordinary outdoor sculptures along the Grand Union Canal–a collection he dubbed, “Gerry’s Pompeii.”

Similarly, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, a woman named Helen Martins (1897–1976) transformed her home into “The Owl House,” installing over 300 concrete and ground-glass sculptures in and around the property—the majority of her creations, owls.

And in Homestead, Florida, coral sculptor Edward Leedskalnin (1887–1951) constructed a colossal castle out of oolite limestone, featuring behemoth-sized stone sculpted into a variety of shapes including slab walls, tables and chairs, a water fountain, a crescent moon, and a sundial.

These individuals represent just a small sampling of the countless known and unknown “outsider artists” around the globe, each with his or her own infinitely fascinating backstory; Gittins among them.

Christopher Lee-Power

In a chance encounter in 1987, Gittins met future Liverpool-based TV and film actor, Christopher Lee-Power, while riding the same bus; an encounter Lee-Power credits to launching his professional acting career.

Upon meeting, Lee-Power confided to Gittins that as a child, he’d witnessed the murder of a friend of his father (who was also stabbed during the incident). Following the ordeal (which, or course, had devastating effects on his entire family) he was diagnosed with hyperactivity and placed in a psychiatric hospital–continuing to suffer speech difficulties and PTSD-like symptoms well into his teens.

At age 16, Lee-Power finally dropped out of school—convinced that his aspirations of becoming an actor could never come to fruition.

As Lee-Power explained in an interview in Echo magazine, Gittins took the self-defeated 19-year-old aspiring actor under his wing, personally worked with him to correct his speech impediment, and encouraged him to enroll in the prestigious London Acting College–while teaching him the finer points of drama and art.

According to Lee-Power, “We visited several art galleries, where he shared his knowledge of the great artists, and he even encouraged me to read aloud from books to boost my confidence. As the years passed, I honed my acting skills and voice under his tutelage.”

Awarded a “Diploma in Acting” from Oxford University in 1996, Lee-Power then attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and was later accepted to the famous Lee Strasberg Studio, in London.

Since that time, Lee-Power has built a career as a theater actor, has landed several TV roles (including a part on the popular Coronation Street), appeared in six feature films, and in 2009 published his autobiography, Breaking Free–From the Street to the Stage, which inspired the film, Free to Be.

On multiple occasions, Lee-Power has credited Gittins for this success.

When Art Re-Defines “Art”

When Gittins’ family visited “Ron’s Place” (the only name that seemed appropriate) after his death in September of 2019, what they found inside left them stunned and speechless—even though they had an inkling of what to expect.

The first thing they encountered was an enormous Minotaur head staring back at them; its immense gaping maw the hearth of a fireplace. Above it, ancient Greek dramatists–Euripides, Aeschylus, Sophocles–adorned the wall.

On one side of the mythological beast was an array of handcrafted military paraphernalia–tabards, shields, helmets, and various weapons—while dismembered human body parts (sculpted from newspaper) adorned the other; limbs, torsos, and heads were scattered near the adjoining bay windows.

To the right of the “Minotaur Room” is the central corridor, painted floor-to-ceiling with ancient Egyptian iconography; profiles of Osiris (Lord of the Underworld) and Horus (the falcon-headed god), beneath life-size depictions of a Cleopatra-like pharaoh—embellished with evocative signs and symbology.

Next is the aquatic-themed bathroom—alive with manta rays, hammerhead sharks, and all sorts of sea creatures seemingly swimming across the walls (and inhabiting the room).

Then comes the “Georgian Room,” filled with portraits of famous naval figures, and the first fireplace Gittins ever created; comparatively simple, its feet are fish.

Across the hall is the “Lion Room,” which features trompe-l’oeil friezes (scenes intended to fool the eye with optical illusions), including an area of faux chipped stone and a horse playfully smiling, which faces Gittins’ most technical masterpiece: a spectacular lion fireplace—rendered flawlessly.

Virtually every surface of the apartment had been incorporated into the massive work of art—and surely would have been all-inclusive, had the artist lived.

Before that visit to “Ron’s Place”ended, the family knew that something had to be done to preserve the apartment and all the art it housed. But none of them could legally lay claim to it.

Enter: Martin Wallace

One of the first to agree with the Gittins-family assessment of “Ron’s Place” was Martin Wallace, a 55-year-old BAFTA-nominated filmmaker (The British Academy of Film and Television Arts) who was amidst creating a documentary series called, Journeys Into the Outside; the focus of which was traveling the globe to investigate extraordinary places built by every-day people. And after seeing Gittins’ Oxton apartment, Wallace knew that featuring Gittins and his art could go far to preserving it.

Acting as a self-appointed “trustee,” Wallace continued to pay the rent on the apartment; both to buy time for a more permanent solution, and to guarantee continued access. But things quickly got complicated.

By 2022, since no one was actually occupying the residence, landlord and owner, Salisbury Management Services, decided the building would be sold at auction. (It was old and deteriorating and too costly to restore).

Additionally, Wallace and the Gittins family were not aware that sometime before (while Gittins was still a resident), the original owner had sold the property, and with that sale went any agreement allowing Gittins to modify the interior.

The Caravan Gallery

With the auction date set, Gittins’ niece, Jan Williams, and her partner, Chris Teasdale, two artists who work under the name The Caravan Gallery, suddenly entered the fray–dedicated to finding investors to purchase the property and save the art.

Having formed a new business entity called, “The Wirral Arts and Culture Community Land Trust,” they figured it was just a matter of holding Salisbury Management Services at bay long enough to find willing investors.

But as the auction date neared, it became apparent that what they needed to happen, wasn’t going to happen quickly enough. So, they agreed on a plan “B”: They applied to the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England to have the building (and its contents) designated an “Historic Building.”

Salisbury Management Services was, of course, furious.

Enter: Tamsin Wimhurst

On the eve of the auction, as Jan Williams nervously paced the floor, hoping for a last minute miracle, she received an unexpected Email from a woman named Tamsin Wimhurst that read, “Just heard [the flat] is up for auction today. I would like to loan you the money needed.”

Tamsin Wimhurst, a 57-year-old heritage and history authority from Cambridge with a passion for rescuing unique properties, had been leafing through a day-old copy of the Guardian when she saw the notice about “Ron’s Place” being put up for auction.

Wimhurstn, and her husband, Michael, had rescued the “David Parr House” in 2014 (a Cambridge terraced house brimming with beautifully preserved, intricately designed interiors from the Arts & Crafts Movement [1880 and 1920]), so she immediately contacted her husband with her plan to save the Gittins house. They had only hours to do it.

The following morning, though no money had as yet changed hands (Williams had only Wimhurst’s assurance), Wallace placed a bid on the group’s behalf–learning then that there was one other offer on the table.

Ten minutes after the auction closed, Williams’ phone sounded. Theirs was the winning bid! The house was theirs!

Now they just had to keep the dilapidated house from falling in on the art they fought to preserve.

Restoration, Preservation, Status

The fight to preserve Ronald Geoffrey Gittins’ “outsider art” legacy had drawn such media attention that when fundraising began to renovate the property to make it safe and welcoming to the public, donors began lining up.

But little did Williams and her group imagine that an anonymous benefactor would step in in 2023 and buy the property (designating it for creative arts programs to prom.

References

ronsplace.co.uk., “Ron Gittins: the man who built a Roman altar in his kitchen,” About Ron – Ron’s Place (ronsplace.co.uk)

www.bbc.com., “Ron’s Place: Artistic Fantasy World Gets Listed Status,” Ron’s Place: Artistic fantasy world gets listed status (bbc.com)

cambridge.org., “Ron’s Place: the Theatre of (Personal) Power,” https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/epidemiology-and-psychiatric-sciences/article/rons-place-the-theatre-of-personal-power/4D958625CF82E226060E2D41A7D810B7

telegraph.co.uk., “The Michelangelo of Birkenhead: How Ron Gittins Turned a Dingy Flat into a Gigantic Artwork,” https://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/artists/michelangelo-birkenhead-ron-gittins-turned-dingy-flat-two-storey/

longreads.com., “Ron’s Place,” https://longreads.com/2023/07/13/how-an-extreme-diy-project-sparked-a-debate-about-art/

liverpoolecho.co.uk., “Actor’s Chance Encounter with Recluse Changed His Life,” https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/coronation-street-actors-chance-encounter-20689920

en.everybody.wiki.com., “Christopher Lee Power,” https://en.everybodywiki.com/Christopher_Power

historicengland.org.uk., “Historic England,” https://historicengland.org.uk/about/what-we-do/